This blog-post has earlier been posted on the Social Theory & Health blog.

Roar Stokken

Associate Professor, Volda University College, Norway

In 2018 I hosted a seminar on the quality of patient education. The twenty-two participants worked at patient education resource centers in Mid-Norway and together had more than hundred years of professional experience in the field (1).

A core aim of the seminar was to identify groups of stakeholders and to discover how these group’s understanding of quality regarding patient educative initiatives were perceived. The extent and nature of the variation in how participants described the different groups during the seminar underlies this short blog.

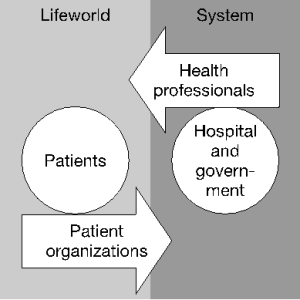

Four main groups of stakeholders that were in a legitimate position to claim that their demands be met were identified: 1) users and their families, 2) hospital and government, 3) health professionals, and 4) patient organizations.

Regarding users and their families, the impression was that they wanted to gain knowledge about the relevant condition, but even more importantly, was to be seen, heard, be met with empathy and compassion, be given attention, be involved etc. In terms of Habermas’ theory, these concepts belong in the lifeworld, where consensus, solidarity and loyalty are the main interpersonal regulatory factors (Habermas, 1984).

Predictably, the demands emanating from the hospital and the government were bound to the system, in Habermasian terminology, via demands for fewer readmissions, documentation, standardization, efficiency, and also that the educative initiatives comply with growing trends within the sector in terms, for example, of inter-professional collaboration and digitalization.

Regarding the demands from health professionals, the impression was that they want a patient educative initiative to be grounded in professional knowledge, proven to be effective, and to result in more autonomous patients who take responsibility for their lives and their decisions. In addition they wanted an initiative that results in a high rate of participant satisfaction. In terms of Habermas again, this signals an educative initiative originating in the system, as is indicated by concepts like professional knowledge, effectiveness and responsibility. They also wanted the new knowledge to impact upon the daily lives of the patients, which necessarily implies changes in the lifeworlds of the patients.

The fourth group of stakeholders comprised patient organizations. These demanded to be involved in educational initiatives on equal terms with the professionals. This demand for ‘equality’ suggests a lifeworld source or character; but they also had demands that, though originating within the lifeworld, have systemic consequences. Specifically, they wanted educational initiatives that showed clear gains for their group of patients. More generally they were insistent on improved services for their members.

To sum up at this juncture, the demands from the patients reside within the lifeworld, the demands from the hospital and the government reside within the system, and the demands from the professionals originate within the system while aiming at consequences with the lifeworld. None of this should occasion surprise. Nor is the patient organizations’ attempt to change the system on the basis of experiences within the lifeworld unexpected. The interesting part, I suggest, is that patients’ organizations demand equality and full reciprocity with professionals.

This demand for equality requires that the relationship be based on communicative action, that is, one actively oriented to consensus amongst all parties, rather than strategic action, that is, one openly or covertly swayed by money and power. For Habermas this is important, since it gives patient organizations the opportunity to engage as equals rather than as ‘puppets’ of the health care system.

When patient organizations’ agenda is to maximize their impact on the system, the media and the logic of the lifeworld ‘confront’ those of the system. A key question then is: can demands that originates within the lifeworld be communicated ‘on the premises of the patient organizations rather than the premises of the system’? Obviously, giving the professionals the responsibility to translate between the media of the lifeworld and the system is giving them power over the translation. On the other hand, since the process of translation is an integral part of the communicative action between the parties, the consequences of the translation themselves have something of the character of communicative action. So this process of translation is not giving the professionals the upper hand, but rather allocating to them the demanding task of being responsible for aligning the system and the lifeworld.

The patients organizations demand for equality between users and professionals is a sense the antithesis of the professional demand for an educative initiative that derives from professional knowledge, effectiveness and responsibility, and that denotes changes in the lifeworld of the patients.

In the diverse stakeholders demands concerning quality of patient education there is as such a kind of equilibrium between the system and the lifeworld, and the impact these have upon each other. This does not come out of thin air. It is actually a result of generally accepted guidelines the professionals ‘ought’ to follow.

In 1997, a pilot patient education resource centre was established at Aker hospital in Oslo. This was founded on an ideology where users and professionals should be equal. For instance the steering committee was made up of 50% users’ representatives and 50% professionals (Stokken, 2013).

Later, this pilot initiative became a national resource centre. This led to the ideology of equality between users and professionals becoming institutionalized and disseminated in «The standard method for quality development of patient education», which specifically demands equality between users and professionals during the planning, delivery and evaluation of patient educative initiatives (Stokken, 2013).

Making equality between users and professionals, hospitals and patient organizations into a standard aspiration or requirement made sense in the context where users’ organizations and health care system were on an equal footing. In other contexts it can be challenging to the health workers, e.g. in terms of contradicting the demand for rationally justified choices within the hospital sector and the fact that professionals are employed while users take part voluntarily.

To conclude, as I understand it, the impressions of the demands from the patient organizations that participants at the seminar put forward are a direct consequence of the standard method championing equality and reciprocity. By evoking a lifeworld concept, penetrating the system, to describe the relationship between patient organisations and hospitals, there seems to be a kind of equilibrium involved in the exchange of media between the system and the lifeworld that at least reduces the colonizing forces the system have over the lifeworld.

(1) Note on patient education in Norway: Patient education became legislated in Norway in 1999 as one of the four main tasks of hospitals, along with treatment, research and the education of health professionals. In Norway 99% of all hospital stays are publicly funded. Thus, patient education under the auspice of hospitals has the entire Norwegian population as its target group. Guidelines require it to be planned, delivered and evaluated in equal collaboration between users and professionals.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press.

Stokken, R. (2013). (Un)organizing equal collaboration between users and professionals: on management of patient education in Norway. Health Expectations, 16(1), 32-42.