Written by Professor Sarah Hean

IMPROVING COLLABORATIVE WORKING BETWEEN CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES: THE HORIZON2020 FUNDED MSCA RISE PROJECT REACHES THE HALF WAY MARK

Effective collaboration between mental health (and other health/welfare services) and criminal justice services impacts on mental illness and reduces reoffending rates. The Change Laboratory Model (CLM), a model of workplace transformation, has potential as a tool to promote interagency collaborative working and innovation. However, the CLM, highly successful internationally and in other practice contexts, is new to service development in the criminal justice context and requires validation before implementation

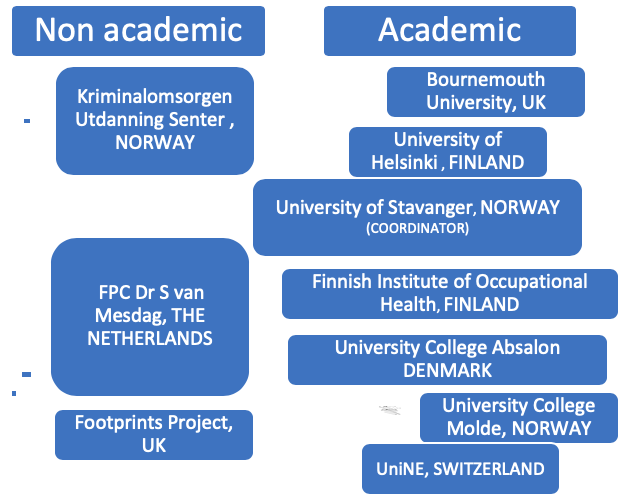

COLAB, a consortium of researchers and professionals 10 European institutions, funded by the EU Horizon2020 MSCA RISE programme (2017-2021), explores the adaptations that need to be made to the CLM to maximise the likelihood of its success upon future implementation in this new environment.

The specific objectives for the project were to:

- Objective 1: Validate the Change Laboratory Model, ready for implementation

- Objective 2: Run interactive knowledge exchange events between CLM researchers and experts in other models of collaboration and innovation.

- Objective 3: Develop a training programme to increase awareness, positive attitudes and competence in Change Laboratories in the criminal justice context

Work performed 2017-2019

Eleven empirical studies are underway exploring collaborative practices within the criminal justice services from offender and professional perspectives in two European contexts (Norway and England) and a variety of contexts including low security prisons, third sector organisations, half way houses and diversion/liaison services. A further nine projects explore the potential of piloting the CLM in some of these contexts and the development of training resources to help support collaborative practice.

Findings to date are:

Preparing offenders for resettlement and a life free from crime is complex, an interplay of different state, private and third sector actors. Effective collaboration between all actors, including offenders, is required to navigate this system effectively, but challenges include:

- Fragmented or compartmentalised work activities and blockages in information sharing. This leads to knowledge disparities between agencies and reliance on informal and personal interagency relationships.

- Lack of contact between agencies

- Structural challenges to collaboration at an intra and interagency level

- Diverse adaptation of national policies at a local level (e.g. national models of rehabilitation, diversion/liaison in England and the Import Model in Norway)

- A dependence on cooperation from vulnerable clients.

- Limited time, staff and financial resources leading to a depreciation in value of holistic work activity

- Tensions caused by a lack of shared meaning between actors when using workplace tools designed to promote collaboration

- Workplace structures not keeping up with a change from security/control to a rehabilitation focus.

- Lack of effective service user involvement strategies

These challenges mean professionals do not have the confidence, knowledge and competence to support vulnerable offenders in achieving their goals of life stability, meaning, hope and feelings of self-worth they need to manage a future without crime.

Each of these challenges is a potential subject for researcher-facilitated models of workplace change such as the CLM, in which multiple voices can be merged in a process of bottom up innovation or service redesign. However, the CLM in its current form faces political and logistical challenges. These relate to the need to negotiate a mandate to implement the CLM and the flexibility of methods used once implementation is agreed.

There is a need:

- To build strong, long term practice-academic relationships based on national reputation, trust and logistical ease.

- For a perceived and mutual understanding of the need/demand for organisational change, the description of which is shared by all actors.

- For creativity when negotiating limited human and financial resources available for innovation and collaboration in these organisations. Everyday service delivery and the needs of the offender cannot be compromised in this process.

- For alternative methods to be found to collect mirror data that relies on audio and video recordings when not permitted in high security environments

- To consider possible conflicts, the emotional labour involved of the CLM process and power relations between participants. The CLM must explore tools for supporting participants, especially the offender, during these processes.

- To explore the methodological challenges of researchers working in the secure prison environment and in an international and interdisciplinary milieu.

- For training in the CLM method for criminal justice staff wishing to use these methods as part of their routine service development strategies. Providing training has timing, resource and logistical implications.

- To clarify the relevance of this type of training for front line professionals working with offenders in crisis.

- For a toolbox of tools, to promote and measure collaboration and innovation. Formative interventions such as the CLM are not the only tools to manage organizational collaboration and innovation in the prison system

- To expand on our empirical understanding of what works currently. There is a danger that researchers focus on the contradictions in collaborative practices alone. There is evidence of workplace activity conducted mutually but with flexibility and feelings of autonomy. Professionals from different organisations, work together in a hybrid configuration of actors, with different, potentially competing institutional logics, but have often engaged in learning processes leading to actors being able to oscillate between the institutionalised logic of their own profession and a shared logic centred on the needs of the offender.

COLAB activity has moved forward understanding of the challenges facing interagency collaborative practice in the criminal justice system, capturing the front line professional and offender perspective previously poorly understood.

COLAB findings to date have shown that the CLM has potential in the criminal justice context as predicted, and pointed to areas where organisational change and innovation is required. However, caution must be exercised in future plans for implementation as the model faces political, logistical and methodological challenges specific to the criminal justice environment.

The impact of COLAB activity to date is evident in the articulation of the offender voice in projects that capture the impact of current service provision on offenders experiences. COLAB members have as a result of their secondments now engaged in the development and implementation of a service user feedback strategies. There are reports that COLAB research had encouraged professionals to initiate change in health services in a prison by expanding their treatment capacity and one site has initiated an innovation and service redesign process through agreeing to implement a modification of the CLM. COLAB members and students attending COLAB events have volunteered to work in third sector organisations supporting offenders. Reflections by COLAB members has captured the utility of their experiences to their personal development, insight into the research process and specifically research into interagency working, reoffending and offender rehabilitation in other European contexts. This has improved their ability to cross national, disciplinary and professional cultural boundaries in their practice.